http://www.zimbio.com/pictures/L-oY6KeqzmT/Hidden+World+London+Underground+Night+Shift/GOTEeHxLthr

which shows wonderfully atmospheric images of night workers and explains the work they do.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

es of manufacturing. But would you really care to implicate yourself in al that complexity, even if it does involve other people’s lives? Gursky’s subject is not so much the world out there as an autonomous system in itself, as our reading of this world. His suggestion is not that working life is deplorable and that we must sympathize with its participants, but that we are in no position to come to any conclusions whatever, that we lack analytical capacity even when the evidence is as thick on the ground as it is here. (The Photography Book, 1997:188)

es of manufacturing. But would you really care to implicate yourself in al that complexity, even if it does involve other people’s lives? Gursky’s subject is not so much the world out there as an autonomous system in itself, as our reading of this world. His suggestion is not that working life is deplorable and that we must sympathize with its participants, but that we are in no position to come to any conclusions whatever, that we lack analytical capacity even when the evidence is as thick on the ground as it is here. (The Photography Book, 1997:188)

![clip_image002[6] clip_image002[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjr0mjMxhmD5V2cvcWaNfsb3FYLfQDbMJWjX4hrmrwpz3zrAFibHYwspnxCd0HVrGC4XmNQ3n5PtYMhImXvfKiw_3eDB5j6zJ4xtHKQsGlNKbJJuE5zomT3goj41gh8D3e8mYwmE2vPmkA/?imgmax=800)

| ![clip_image001[6] clip_image001[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiEFkbkg5xJTR_6ZrDYMOCs52dK6ieciAe8oowJvV5O5cfwx5YLZEZdGcmob6yrkALVVsgtR36uY_wNiiU0CLm0mDG01c-qRMaZPV6G9_maqALyY0j0D2wqwh0bQZV3Y4Izok1MO8_0O3Rm/?imgmax=800) |

![clip_image001[8] clip_image001[8]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjutpBe0waxZm7CN2EyjyHcsZby9xSvEQH1wwNYDdJ5ttn28JBzSGzdnbubdQqnOp2N4Ssd1Rdu5a_j6nQ3dbwqwcxO1FdTjzszpOSDFNlj9s1c2D56kHER5AfQZsucQE3DicyY5ytVaQGS/?imgmax=800) | ![clip_image001[10] clip_image001[10]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiXvaSNSb-zgHK8y5X5CpyPRkmhGZ98X87G7HCYrEn2u3Js9_IQBptKao7wNI45Fe71xV4QLq_W-LyBrMXLogHmj7Ez1Lldq3q1UzLnWNqeExFcW1ZAVQiw-ReB3KW9hQK0VUdbXzdri3dO/?imgmax=800) |

![clip_image001[12] clip_image001[12]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgnIHUSnQD9enNm8AhUay_RcNYxUdO8uPiRYPKP7YGNAVG8Na3XSwjyd5vvuLW90IUqHTjNLaUDRlfOxaSJ2h8qsOZObyUMtbYZCo70wYVczNb3opnR_VI4OtXs7xBlAAprl57K71zrrIg/?imgmax=800) | ![clip_image001[14] clip_image001[14]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhTBYAzJVSWgEAqHBOJ2OPTzh3KDKCY6eGch3IhWjf2qwW1dGQGKwAvL3fjIh3mK4WZrQ2aEfpo74NhTZda8bUnGxKzFHrgDnVWYO54RWGmw3_YFiakh5nZa9wj7DQ_Ds4BNB662VbszLH1/?imgmax=800) |

![clip_image001[16] clip_image001[16]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgUtrlF-kpb0mbBZprZacdfUq85qLhH-bTpGGWif3EASH-JM7kKmZP3Jrwt3hMtto7-gFeYzVGdtBcm7DcJ1xxiMyxntjDzsQ96hLoslMJLGIedKK0r2cUBKtrivN5VfYoztSGs1qC_LWw/?imgmax=800) | ![clip_image001[18] clip_image001[18]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg5oHEXDs3XoPvFaTIaIpb1DgvZYbab__FRDW_4G68mL0aj_Pb3qJ_UN3uEdjj3wcWj6j3G4o8qOIvZgp4A9QCdt3QMw8Jekx1IbMPEoazFfTShc2VCEZiFRM5dn8v_eIwwbe5gCOiYvsIS/?imgmax=800) |

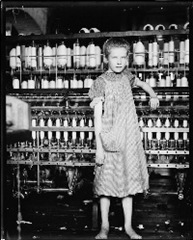

Lewis Hine viewed his camera as ‘a powerful tool for research’ and photographed child workers in an attempt to instigate legislation against child labour.

Lewis Hine viewed his camera as ‘a powerful tool for research’ and photographed child workers in an attempt to instigate legislation against child labour.